Haunting Highlights from the Seaport Museum’s Collections

A Collections Chronicles Blog

By Carley Roche, Associate Registrar

October 10, 2024

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! No, I am not talking about the Winter holiday season or its beloved carols. While I do appreciate a fun ornament, twinkling lights, and fresh snow the actual best season of the year are the weeks leading up to Halloween—at least in my opinion.

The air is crisp, the leaves are changing colors, and children and adults alike are finalizing their costumes. It’s always a fun, care-free time just before the typically more stressful Winter months. Plus there is something for everyone to enjoy right now. For those who enjoy the sweeter side of Halloween there is candy, pumpkin carving, caramel apples, and hay rides; for those who enjoy the spookier side there are haunted attractions, Scream Queen movie marathons, and a strong connection to the occult.

As Halloween is my favorite holiday, I thought it would be fun to highlight some of the more haunting artifacts in the Seaport Museum’s collections.

St. Paul’s Churchyard

“View of St. Paul’s Churchyard” ca. 1890-1915. Silver gelatin dry plate negative. Thomas W. Kennedy Collection, 2016.003.0055

Let’s begin our journey in a classic Halloween setting: the cemetery! This silver gelatin dry plate negative from the Thomas W. Kennedy Photograph Collection shows St. Paul’s Churchyard sometime between the late 19th to early 20th century. St. Paul’s Chapel is located at 209 Broadway, only a short distance from the Seaport Museum, and is part of the Parish of Trinity Church. Originally built in 1766, it is the oldest public church in Manhattan, and its graveyard is even older—dating back to 1697.

St. Paul’s cemetery allowed burials until the early 19th century when New York City’s Common Council passed legislation on March 31, 1823 that banned interment in Lower Manhattan over public health concerns in densely populated areas. During the 126 years of burial services at St. Paul’s Chapel, many well-known public figures were laid to rest there. You can still find their names amongst the gravestones including General Richard Montgomery (1738–1755), hero of the American Revolutionary War; George Eacker (c. 1774–1804), lawyer who fatally wounded Philip Hamilton (1782–1801) in a duel; William Houston (c. 1755–1813), lawyer and Founding Father; and George Frederick Cooke (1756–1812), English actor.

Amongst these names, one has been reportedly sighted as a headless ghost walking through the headstones: George Frederick Cooke. During his life, Cooke’s performances on stage were lauded but his gambling debts and alcoholism led to a poor reputation. While visiting America for an acting tour, he became stranded in New York City during the outbreak of the War of 1812.

He passed away from cirrhosis and was buried in St. Paul’s cemetery shortly afterwards. You may be asking: why is his ghost headless if his body was intact upon death?

It is believed that Cooke sold his head for scientific research to posthumously settle his debts, which led to the headless ghost sightings. Although it has never been confirmed that he did in fact sell his head, Cooke’s skull was found in Philadelphia, PA in May 1930 under the protection of a local physician whose family had the skull for three generations.[1]The New York Times. Cooke Skull Found in Philadelphia. May 12, 1930.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “George Frederick Cooke.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

So the next time you are in Lower Manhattan and want to take a stroll through St. Paul’s Churchyard, keep an eye out for George! It’s believed that his body is wandering around looking for both his former head and his former glory.

Mourning Stationery

Once a loved one has been laid to rest, the living enter a mourning period. Today, this experience is different for everyone. However, during the late 19th century in America, English Victorian ideals permeated society and pushed people to mourn publicly. Grieving people were expected to follow formal rules if they wanted to keep a high social standing in society.

At that time, mourning could last up to two years depending on one’s relationship with the departed.[2]De B.R. Keim. Handbook Of Official And Social Etiquette And Public Ceremonials At Washington. 1889. This period impacted the appearance of family members and household staff. Specialized clothes, from outerwear to undergarments, were worn throughout the mourning period with some loved ones fashioning accessories from the deceased’s hair. The living also draped their furniture, carriages, and even work animals, such as horses, in dark curtains to publicly show that they were grieving. Our friends and colleagues at the Merchant’s House Museum and Center for Brooklyn History have plenty of resources and events related to 19th mourning. Check out their resources if you would like more information.

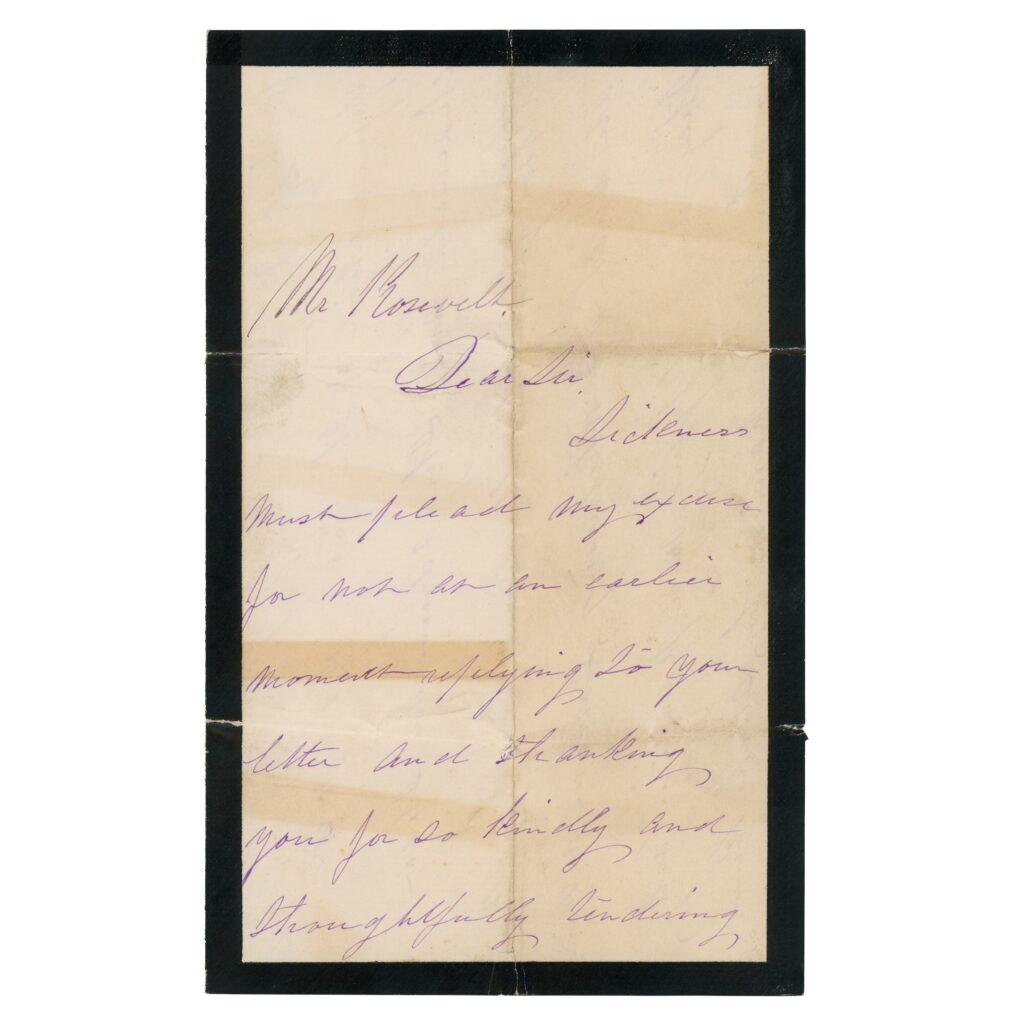

Thanks to mourning stationery, public knowledge of one’s mourning could also be perceived by someone living a great distance away. Personal letters, envelopes, and calling cards became emblazoned with a black border—as you see in this January 25, 1877 letter from Emeline Seaman to George Rosevelt.

The thickness of the border indicated how deep the mourning process was for the writer, with the black edges becoming thinner over time.

“Letter from Emeline Seaman to George Rosevelt” January 25, 1877. Gift of Winslow Foster, 1981.004.0051

The use of mourning papers has been recorded in Europe since the 17th century, but it became popular in the United States after the passing of Prince Albert (1819–1861), husband to Queen Victoria (1819–1901). She entered a deep state of mourning for the rest of her life, only using black-bordered stationery until her own passing to show her deep love and respect for her husband.

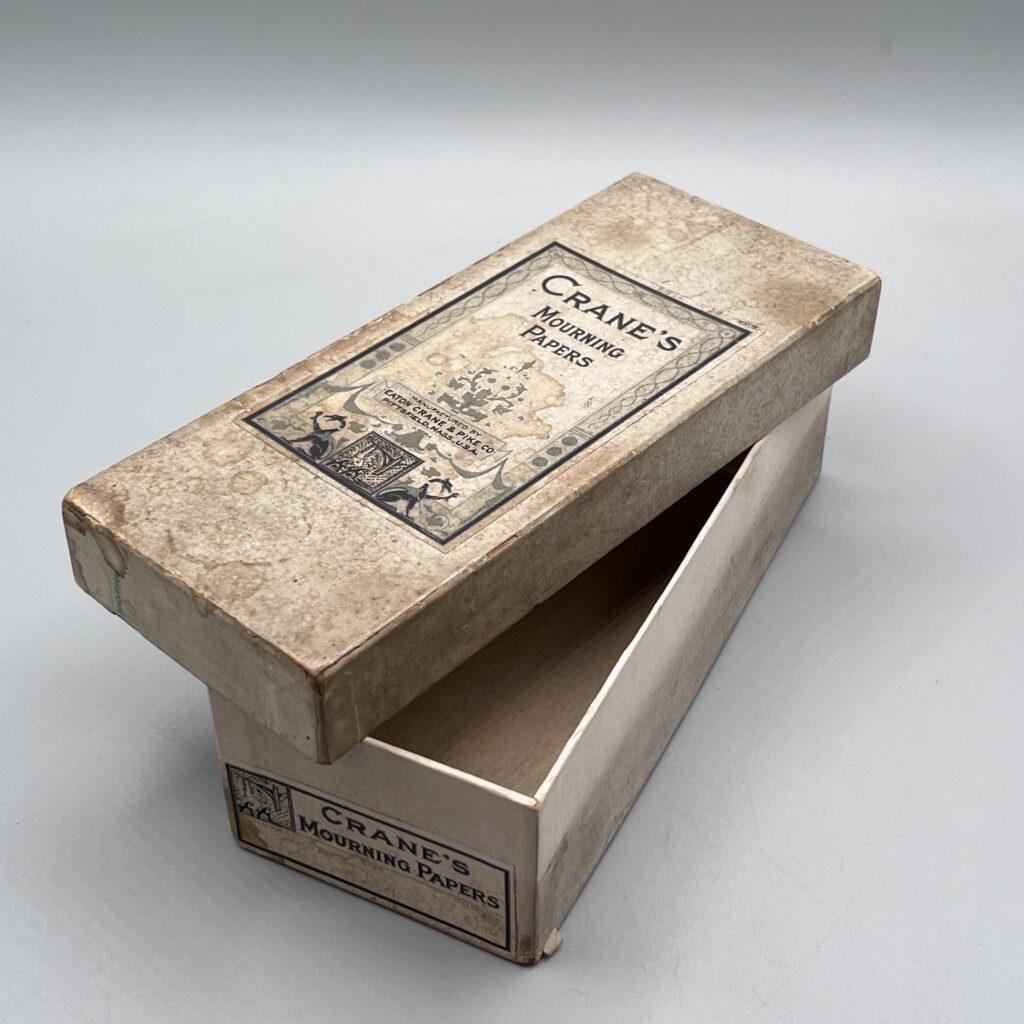

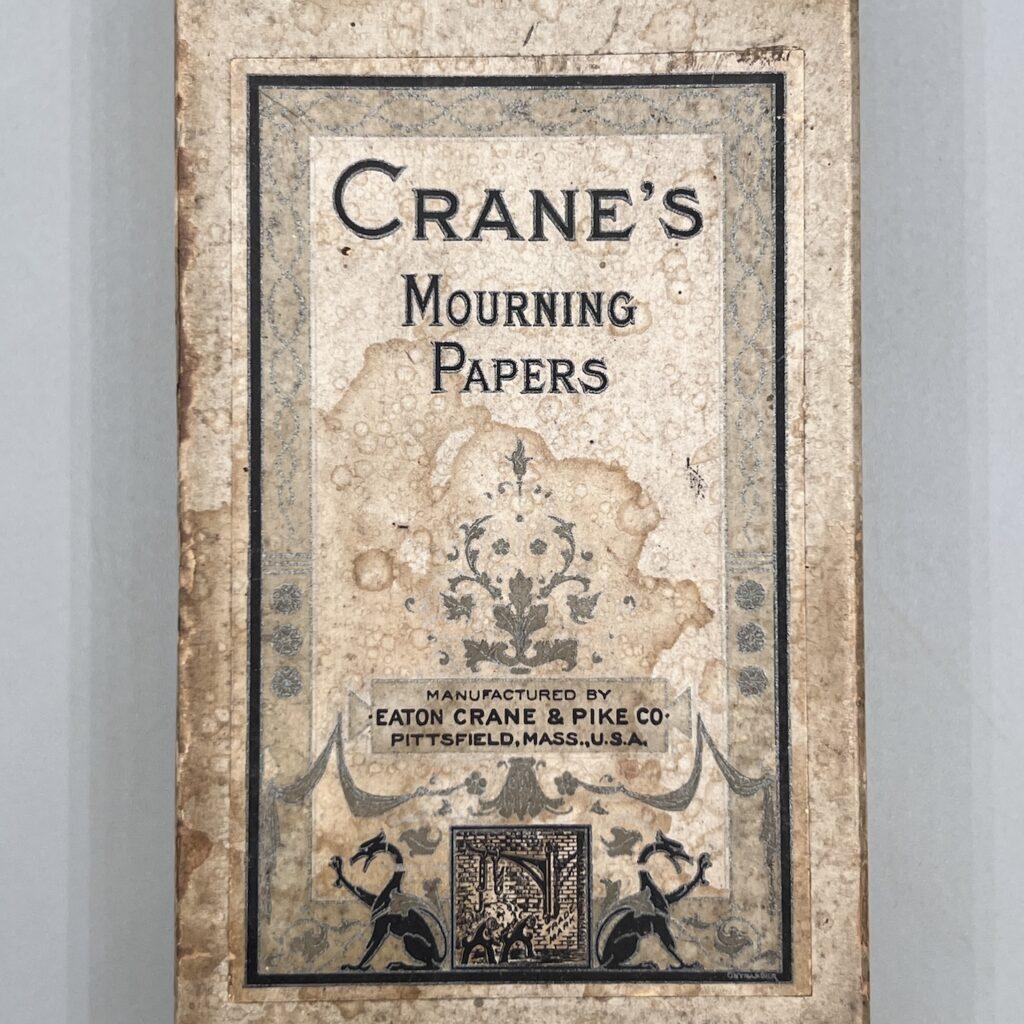

“Crane’s Mourning Papers Box” early 20th century. Gift of Francis Lammer, 1976.028.0006.a-.b

With mourning stationery’s increased use in America, paper companies began to print pre-packaged letters and envelopes for customers. This box and its previous contents were manufactured at Eaton, Crane, & Pike Company[3]Learn more about papermaking at Eaton, Crane & Pike with this article by the Berkshire Historical Society at Herman Melville’s Arrowhead, a once prominent paper-based company in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Although the use of personalized stationery has fallen out of fashion in the modern digital age, I find it interesting to see such public access to one’s personal grief.

Thumb Skulls

The first time I saw a human skull in person I began to feel disoriented. Logically, I know that everyone has a skull, but it is safely tucked away behind a barrier of skin and muscle. Before this moment, I had only ever seen skulls in visual media and they always symbolized danger, finality, and death. So, seeing a skull in the flesh (or rather out of the flesh in this case) put into perspective my own mortality.

For centuries, artists across different cultures have used skulls to represent death. This iconography is its own subsection of art known as “Memento Mori” a Latin phrase that translates to, “Remember you must die.” Most often featuring a skull as its central image, memento mori art also utilizes hourglasses, clocks, flowers, fruits, and candles to remind viewers of the passage of time and their inevitable demise. Even with this morbid connection, skulls are still prominently used today in fashion, media, and literature.

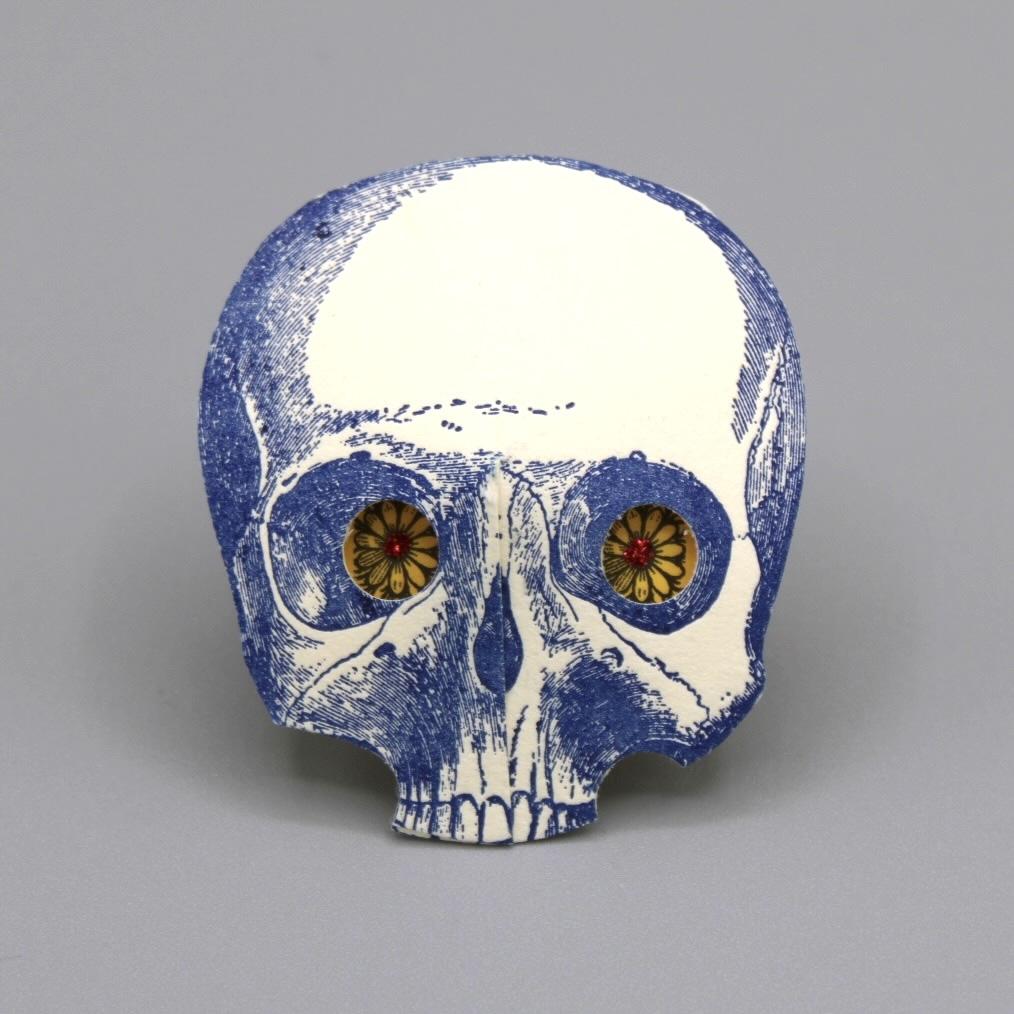

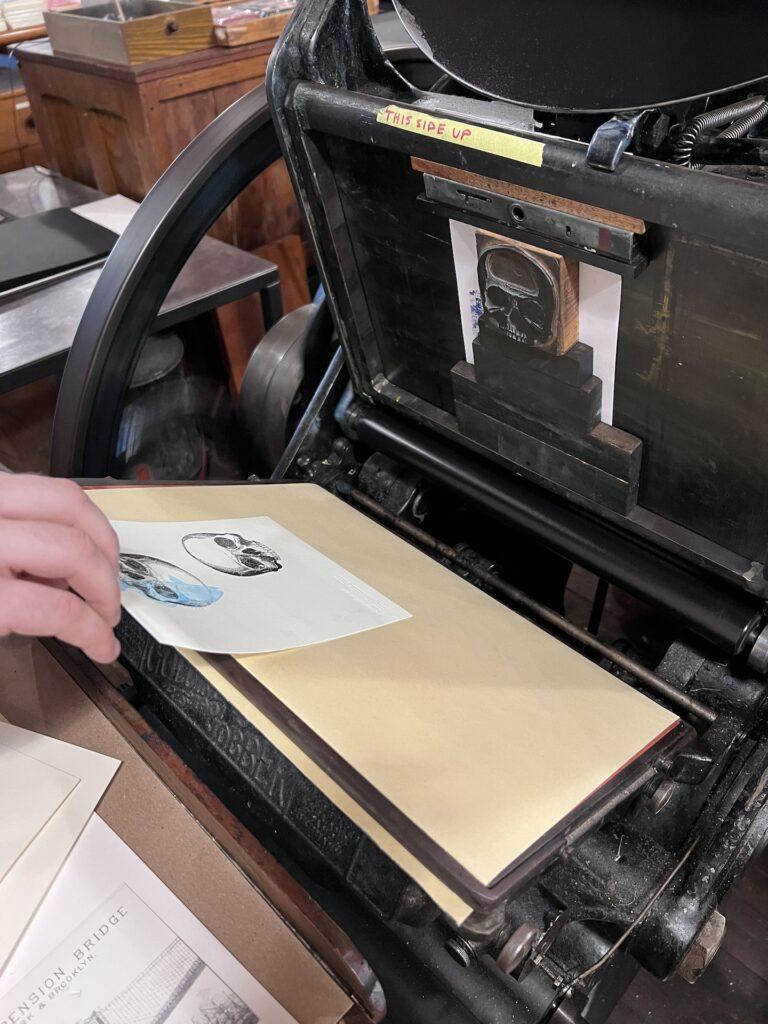

But skulls don’t always need to carry such heavy meanings. Robert Warner (1956–2023), former Shopkeeper and Master Printer at Bowne & Co., utilized skulls in his artwork frequently creating lively and bright collages. Known as Thumb Skulls, because the maker uses their thumb to fold a 2D skull print into a 3D paper sculpture, these designs fall under three categories once complete: wearable as a pin, standalone as just the skull, or a full-body piece of art.

“Thumb Skull” ca. 1990-2020. Mixed media. Robert Warner Works on Paper Collection, 2023.008

I recently spoke with Robert Wilson, current Art Director and Operations Manager at Bowne & Co. as well as close friend to Robert Warner, about the Thumb Skulls to get a better understanding of how they are made. He recounted how Warner used a technique that Wilson referred to as Action Printing (a term not be used by Warner himself), which allows the maker to recycle printing materials by adding new designs at a later date.

Warner would take a previously used paper, postcard, greeting card, photograph, etc.—anything still flat that could be fed into a letterpress machine. A new design was set in the machine and Warner would easily combine the old with the new creating a unique design. The newly created design could be cut, punched out, or added to with beads or fabrics. For Thumb Skulls, Warner frequently added vintage fabric pieces and beads, or modern pipe cleaners to his designs; he had a knack of mixing vintage with modern, from designs to tools, which Wilson describes as “very charming.”

As seen with Warner’s Thumb Skulls, a skull doesn’t always need to be macabre. He created colorful and whimsical works on paper from recycled materials because he could see new ideas in old designs.

Thirteen Club

I do not consider myself to be superstitious, only mildly-stitious when it comes to my favorite sports teams. Despite this, I still know all of the actions to avoid bad luck: don’t walk under a ladder, don’t cross paths with a black cat, don’t spill salt, don’t open an umbrella indoors, and definitely do not interact with the number 13.

For Captain William Fowler (1827–1897), the number 13 was just a part of life rather than something to fear. He graduated from Manhattan’s Public School no. 13 at age 13, he fought in 13 Civil War Battles, in his profession he built 13 structures in New York City, and he belonged to 13 different secret social organizations throughout his life.

Captain Fowler claimed the number 13 for himself and wanted to push back on its negative connotations by founding the Thirteen Club.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Captain William Fowler.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

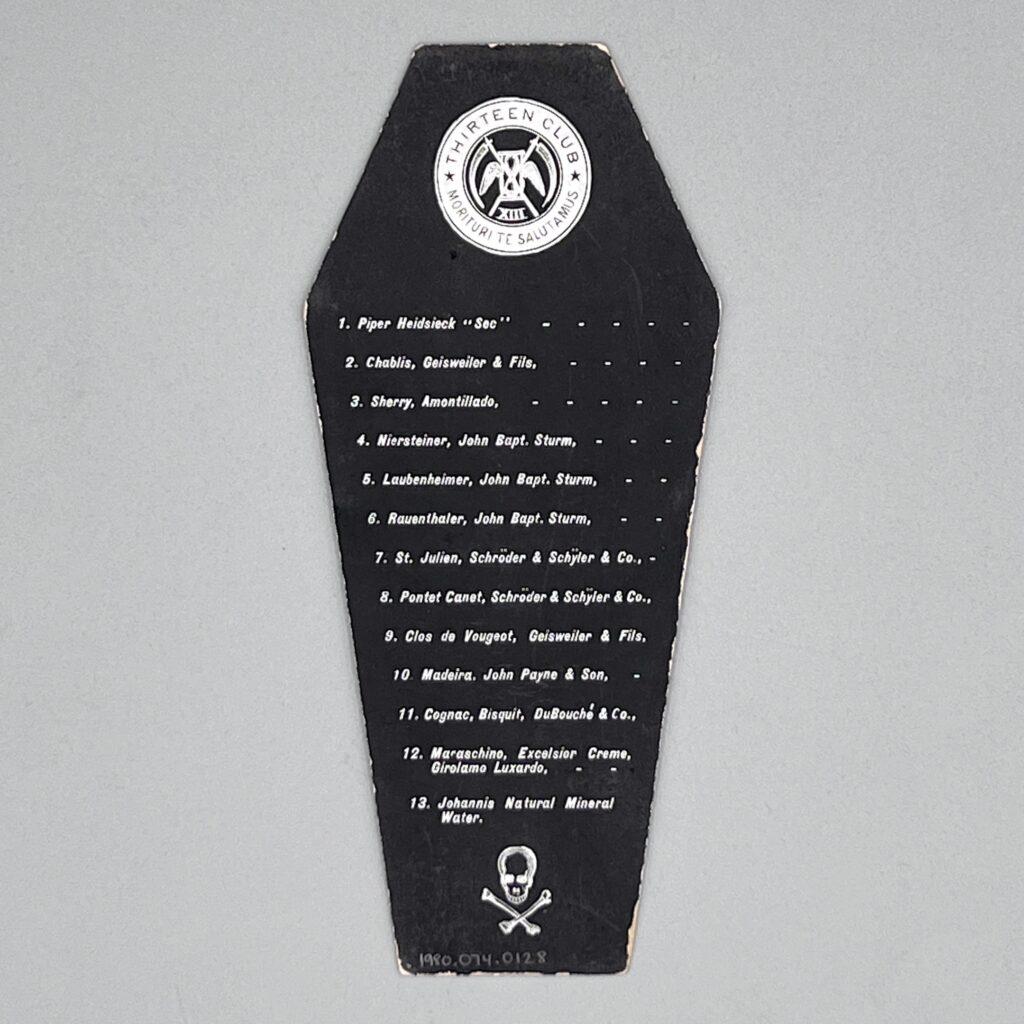

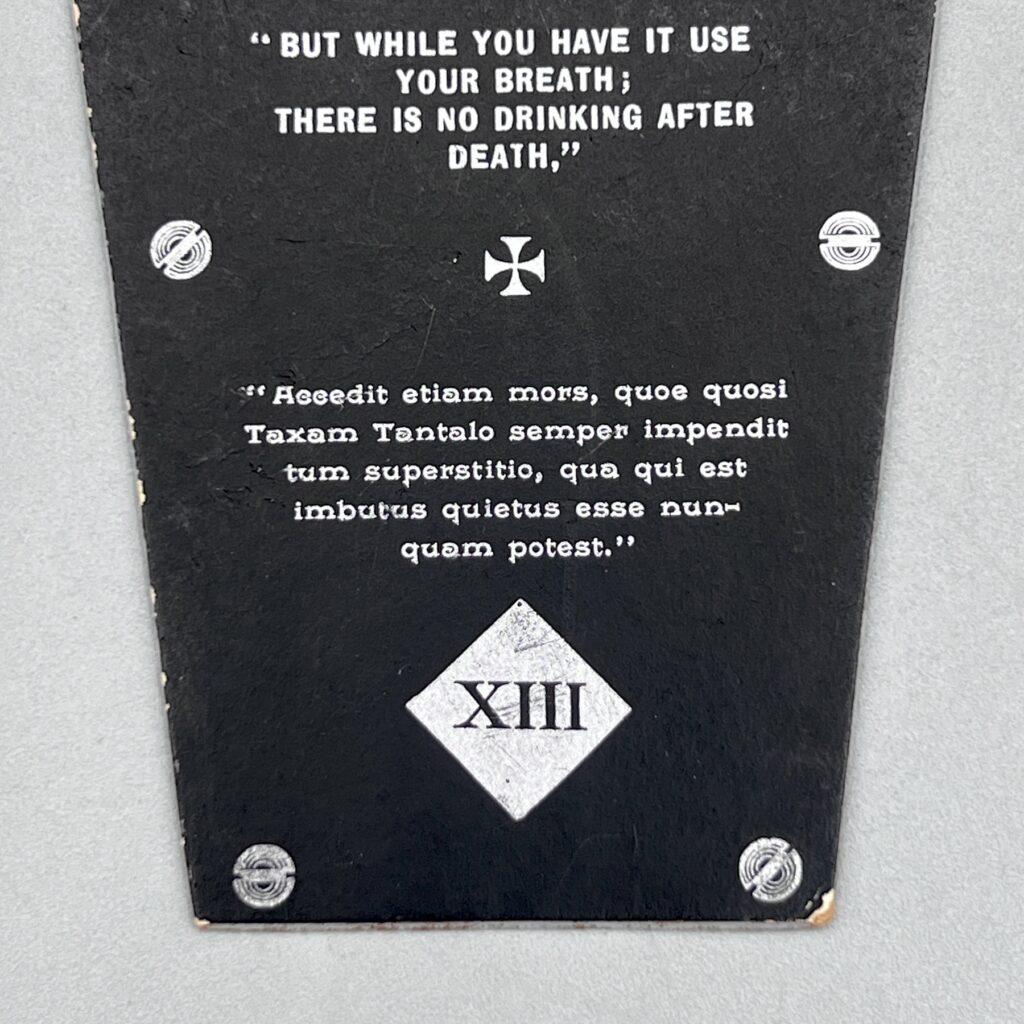

The first meeting occurred on Friday, January 13, 1882, at 8:13pm, in room 13 at the Knickerbocker Cottage (located at today’s 6th Avenue and West 28th Street), which was owned by Captain Fowler. He and 12 additional men came together to debunk superstitions by enjoying a 13-course meal under a Latin banner reading “Morituri te Salutamus” or “Those of us who are about to die salute you.” Captain Fowler’s club became a roaring success with all 13 members surviving and even prospering over the next year. This led to more meetings held on Friday the 13th with 13 drink options as seen on this wine list from one of the later dinners.

“The Thirteen Club Wine List” ca. 1887- ca. 1909. Gift of Mary Moncure Miller and family, 1980.074.0128.

Notice the Latin inscription on the wine list. The translation reads, “There is also death, with which Tantalus always spends a tax on anyone, as well as fear, with which he who is imbued with it can never be quiet.” Whether you are superstitious or not, one main takeaway from the Thirteen Club can be appreciated by all: enjoy life as it is now because we do not know for certain what comes next.

209 Water Street‘s Iron Coffins

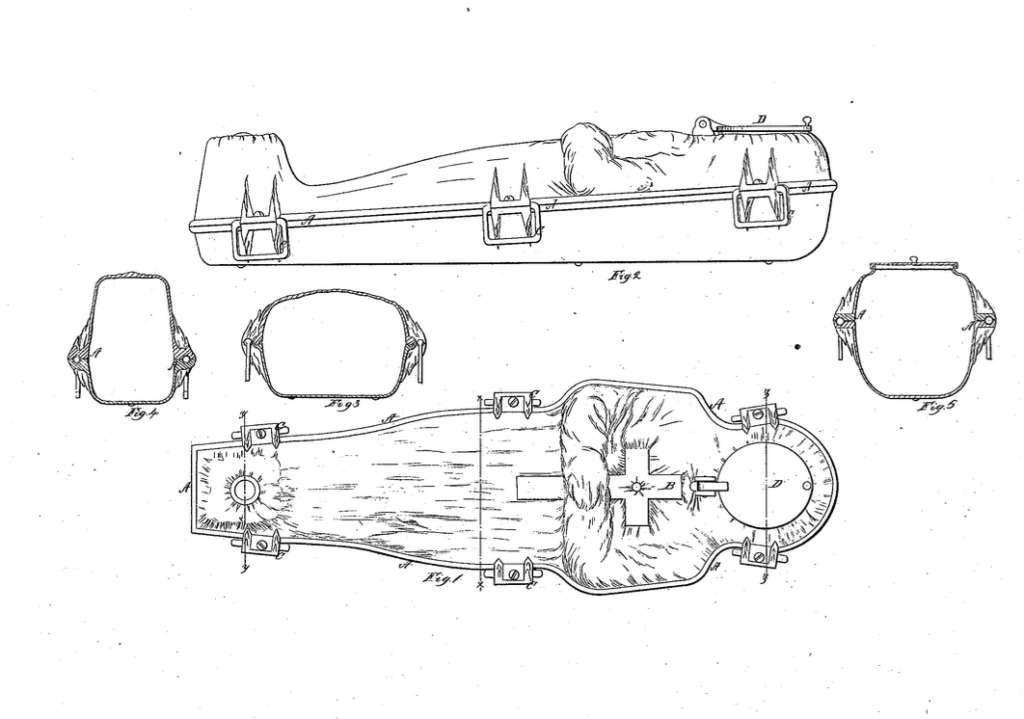

The Seaport Museum has many deep historical connections to the Port of New York. But did you know that there is also a connection to the invention of iron coffins? At 209 Water Street, now home to Bowne & Co., Stationers, stoves and boilers were sold by a man named Almond Dunbar Fisk (1818–1850). After the passing of his younger brother, William (d. 1844), in Oxford, Mississippi, the Fisk family could not proceed with proper burial rites or a funeral due to the distance of their family burial plot in Chazy, New York. Without the modern tools of refrigeration and embalming, William’s body could not be transported back home safely. This deeply affected the Fisk family, prompting Almond to use his knowledge of air-tight structures for his stoves to develop iron coffins.

On November 14, 1848, Fisk received the patent for his “Air-Tight Coffin of Cast or Raised Metal.” These new air-tight and waterproof coffins safely transported deceased bodies across the country without the fear of decomposition or spreading disease. Fisk’s design even included a small window at the head, so families could confirm the death of a loved one and say their final goodbyes.

A.D. Fisk, inventor. United States Patent Office, publisher. “Coffin Patent No. 5,920” November 14, 1898.

After receiving the patent, Fisk founded Fisk & Raymond, Co. with his father-in-law Harvey Raymond (1794–1859) to sell the new Fisk metallic burial cases. In July 1849, the business gained national attention after the death of former First Lady Dolley Madison (1768–1849) who was placed in one of their coffins for public viewing in Washington D.C. The sudden success of the business prompted the two men to open a showroom at 401 Broadway in New York City while utilizing Fisk’s stove and boiler shop at 209 Water Street as the coffin shipping depot.

Unfortunately, Fisk’s good fortune quickly ran out. In September 1849, a fire destroyed his iron foundry in Queens along with the majority of his coffins. He had to use his coffin patent as collateral for refinancing his business. On October 13, 1850, Fisk passed away from an unknown cause and never saw his business find success again.

Captain Ley Ghost Story

What better way to end this list than with a ghost story? This handwritten transcription comes from the Captain Frank Ley Photograph Collection. In the early 1980s, the Museum’s former historian and curator of historic ships, Norman Brouwer, had a conversation with Capt. Ley, which led Brouwer to record multiple stories including these two:

“There were two storerooms all the way aft—on the port quarter for stewards dry stores—on the starboard quarter for deck supplies, paint, etc. Each storeroom had portholes facing aft and to the side. Steward had only key to port storeroom. Frank had only key to stbd. [sic] storeroom. Frank went aft to open the storeroom about two in the afternoon. The lock was low so he was bending down as he opened the door. Normally all he saw was a red shellac deck. This time in the middle of the deck he saw a pair of sea boots. Looking higher he saw the sea boots belonged to a figure shrouded in a yellow slicker. He closed the door and backed away so quickly he backed across the passageway into the bulkhead with a thud. Capt. Barker was in his stateroom on the other side of the bulkhead and came out to see what had made the thud. Frank described what he had seen. Capt. Barker opened the storeroom door and looked in, then closed it again. He did not say what he had seen.”

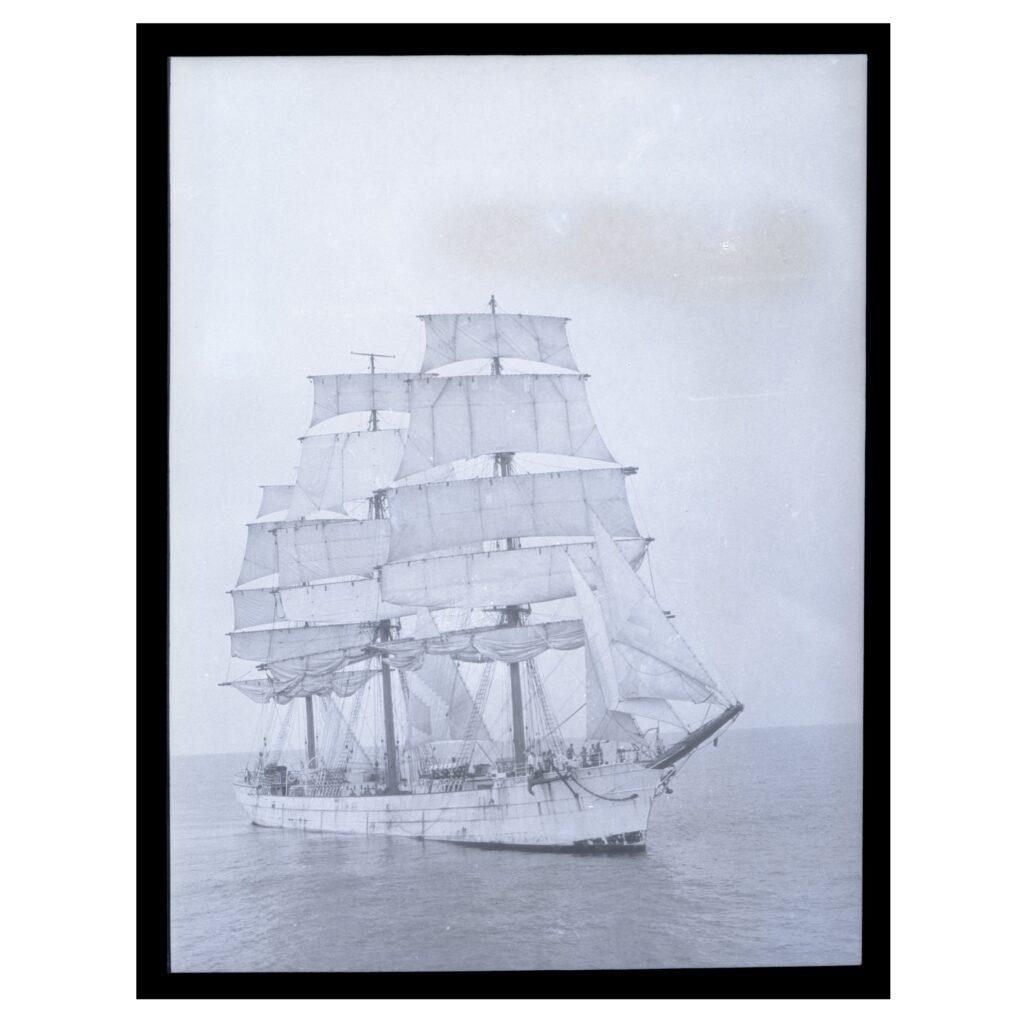

Left: “Tusitala” 1923-1939. Cellulose acetate film. Gift of Terry Walton, 2023.007.0012

Right: “Portrait of Captain Barker on board Vema” ca. 1935-1940s. Gift of Terry Walton, 2023.007.0138

“Later, Barker’s son came aboard TUSITALA and told the following story. Barker’s first command was the (full-rigged ship) DOVENBY HALL. One night he woke up in his stateroom and there was a figure standing over him. He asked what the person wanted but got no answer. While on shore later he met a former steward of the ship who told about a seaman stabbing a captain in his bunk. Barker said, ‘I am the captain of that ship.’ The former steward said, ‘Haven’t you seen the blood stain on the deck? I tried everything I could think of to get it out—limejuice, etc.’ Barker said, ‘There is a carpet on that deck from bulkhead to bulkhead.’ When he returned to the ship he looked under the carpet, and there was the stain.”

Whether you believe in ghosts or not, seeing an unknown figure on a ship or a blood stain will make even the most courageous feel green around the gills!

Trick-or-Treat

With over 28,000 works of art and historical artifacts as well as over 80,000 archival materials in the Seaport Museum collections, the appearance of a spooky tale amongst the stacks was bound to happen.

You can believe the ghosts and supernatural elements behind these stories or simply enjoy the entertainment and historical facts they share.

Either way, I hope you enjoy this amazing time of year with plenty of tricks, treats, and tales from the other side.

“Golden Princess Menu” ca. 1993-1997. Stanley Lehrer Ocean Liner Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation, 2006.029.4514

Additional Readings and Resources

19th Century Mourning a permanent exhibition at The National Funeral Museum.

What do skulls symbolize in art? Exploring the Deep Meanings and Cultural Significance. Musa Art Gallery, June 11, 2024.

Haunted Trinity Church and St. Paul’s Chapel, NYC by Chris Amandier, Buried Secrets. January 8, 2021.

A Brief History of Fisk’s Coffins. Iron Coffin Mummy, February 27, 2019.

New York City’s spookiest, most haunted places. Curbed New York, October 2, 2019.

Death, Burial and Iron Coffins by Scott Warnasch, PBS. September 21, 2018.

Mourning and Black Edged Stationery by Shapell Manuscript Foundation. March 15, 2018.

Friggatriskaidekaphobes Need Not Appl by Joseph Ditta. New-York Historical Society. January 13, 2012.

Morituri te Salutamus by Sadie Stein. The Paris Review. March 13, 2015.

References

| ↑1 | The New York Times. Cooke Skull Found in Philadelphia. May 12, 1930. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | De B.R. Keim. Handbook Of Official And Social Etiquette And Public Ceremonials At Washington. 1889. |

| ↑3 | Learn more about papermaking at Eaton, Crane & Pike with this article by the Berkshire Historical Society at Herman Melville’s Arrowhead |